Understanding the Importance of Extinction

Acquiring a deeper understanding extinction increases our ability to provide adequate species care to those who are at risk of vanishing.

06/17/2024

What Exactly Is an Extinct Species (EX)?

Most people define extinction as a species being wiped out and gone forever. For some species, such as dinosaurs, this is 100% accurate; there are no more of these creatures wandering about in your backyard or anywhere on the planet. Thank goodness for that. But the term extinction is more complicated than that.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List (IUCN 2024) currently uses two categories of extinction. Most people are familiar with the “Extinct” (EX), meaning that a species is gone forever and cannot be brought back from extinction, like our friend, the Parasaurolophus, below. However, since it was 16 feet tall, it might not make a good best friend.

Parasaurolophus from the Cretaceous era, 3D illustration. iStock.com/Warpaintcobra

The other category is “Extinct in the Wild” (EW). In this category, you will find species still alive and present on the planet, but none are in their natural habitats. Extinctions occur for many reasons, including habitat loss, hunting, poaching, disease, and climate change. Extinct species can be classified into two main categories:

- Species that have gone extinct in prehistoric times, including the dinosaurs and other creatures that lived millions of years ago.

- Species have gone extinct in historical times, such as the Dodo bird (Raphus cucullatus), the Great auk (Pinguinus impennis), and the Passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius); both extinctions occurred within the last few centuries.

Extinction is a natural process that has occurred throughout Earth’s history, but recent human activities have greatly accelerated the extinction rate. In 2024, the IUCN listed 908 species as extinct. A study from Brown University has found that extinction rates are skyrocketing, now up to 1,000 times greater than historical background rates, meaning that species are disappearing at an appalling rate, creating losses of critical biodiversity. In an assessment released in 2019, the United Nations reported that an alarming one million species are on the brink of extinction, with the potential to be completely wiped off the planet within the ensuing decades.

What Defines an Extinct in the Wild Species (EW)?

Père David’s Deer is native to China, and by the late 19th century, the species was believed to be extinct in the wild. The photo was taken at Woburn Deer Park. Flickr/Tim Felce (Airwolfhound)

Clearly, there’s not much that can be done for totally extinct species, so let’s focus on those that are Extinct In The Wild. Species that are on the cusp of extinction and only exist in conservation breeding programs, captivity, or in areas outside their normal habitats. Some will sadly slide into oblivion, but there are many that can be helped, with some eventually able to be reintroduced into the wild when conditions are right.

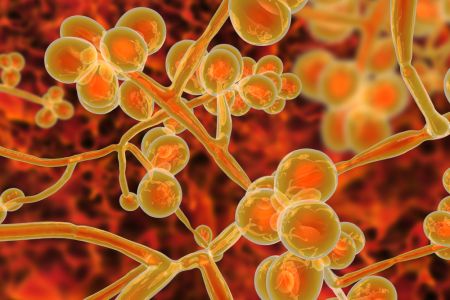

According to the IUCN (2024) Red List, there are 81 species that are extinct in the wild. Because of very limited genetic diversity due to small population sizes, many are in a race against time. Some can be saved when important steps are taken to ensure their survival and our planet’s biodiversity. Obviously, the techniques used to conserve a species are different for animals than for plants, bacteria, fungi, and insects, but all such programs work towards preventing species and biodiversity loss.

While saving a species of bacteria or fungus is not as glorious as saving koalas, many of the lesser-known and unloved species are all part of the web of interdependencies that allow for other species’ survival.

These two below have been rescued but no longer exist in their natural environments.

Extinct in the wild Scimitar-horned Oryx. Jim Black/Pixabay

The Scimitar-horned Oryx (Oryx dammah) is a species of large antelope that is native to the Sahel region of Africa in countries like Chad, Niger, and Sudan. Several other names, including the Sahara Oryx, Scimitar Oryx, and Sabre Oryx, also know it. This antelope is well adapted to life in the arid regions of the Sahel.

They are able to go for long periods without drinking water, instead getting moisture from the vegetation they eat. They are also able to regulate their body temperature by panting and sweating, which allows them to survive in extreme heat.

Extinct in the wild Hawaiian Crow (Corvus hawaiiensis). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Hawaiian Crow (Corvus hawaiiensis) is a beautiful bird endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. Also known as the Alalā, it is a member of the corvid family and is considered one of the most endangered bird species in the world. Its population declined dramatically in the 20th century, and it is now extinct in the wild.

What We Can Do to Help

Spix’s macaw (Cyanopsitta spixii) is native to Brazil and was listed as Extinct in the Wild in 2019 by IUCN. Photo: Etna 1984, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Save Habitats

When possible, the usual intent of programs devoted to saving a species is reintroduction back into its original habitat. Since many of the original problems that led to them being extinct in the wild, such as deforestation, climate change, and pollution, are frequently still present, reintroducing a species into the wild is not always successful or even attempted. When the original ecosystem is no longer present or severely degraded, it can be difficult or impossible to recreate.

Helping species that are Extinct In the Wild or heading in that direction requires a multi-faceted approach if success is to be found. The old saying “an ounce of prevention is better than a pound of cure comes to mind. When original habitats remain primarily intact, steps must be taken to ensure they remain so. Protecting habitats and other factors from human development and other issues we create, like habitat destruction, must occur before tragedy strikes, not after a species is gone. Saving species before they become endangered is far better than attempting to save them later.

Where this has not been done, saving habitats by creating protected areas and working with local communities to reduce the impact of activities such as logging, mining, and agriculture must be undertaken as soon as possible can be effective. Natural processes such as fire and flooding, removing invasive species, restoring native plants and animals, protecting water sources, and increasing connectivity between habitats must be maintained for reintroduction. Climate change and pollution must also be addressed so that the conditions that enable habitats and species to thrive will exist.

Support Breeding Programs

Conservation breeding programs at zoos and other locations need expansion and support. “To maximize effectiveness, the collaboration of the global zoo network with governmental institutions, regional and international trade authorities, NGOs and academia should be fostered,” as reported in the journal PLOS ONE. When these actions are taken in conjunction with habitat protection and development, there are opportunities for successful reintroductions.

Muster Support

Finally, we must raise awareness about the huge numbers of threatened species. Education on the perils that so many of these species face, including our own, can inspire all of us to take action. Most importantly, we all need to elect those who share our values. Without the mobilization of governments by courageous leaders, it is a foregone conclusion that our children will witness the next mass extinction, such as those in the past that eradicated whole branches of species, such as the dinosaurs.

The Fallacy of De-Extinction

There is much talk about our ability to bring back extinct species, such as the woolly mammoth and others. The problem with this is twofold and highly troubling.

Gene splicing might make it possible to restore an extinct species. Still, the technical considerations are considerable, and even if overcome, which they have not been, a cloned, restored species is not the original creature. Such a creature would be missing many factors that were present before extinction. Socialization, diet, stimuli, and viral and bacterial influences would all be missing. Would the recreated creature be the same as his distant, deceased, extinct relations? And without sufficient gene pools, what would be the path to natural reproduction?

An illustration of dinosaur Tyrannosaurus Rex. iStock.com/Chaiyapruek2520

There is also the problem of habitat loss, which currently affects even the “Extinct in the Wild” species we are attempting to save from total extinction. Even if we could bring Tyrannosaurus rex back from extinction, the world in which creatures and similar existed is gone. For various reasons, the environment today is certainly not one that T.rex would thrive in. However, there’s still hope for T-Rex. If we continue with planet-wide devastation with carbon emissions, pollution, and habitat destruction, the climate may be perfect for a dinosaur’s liking. Let’s clean it up first!